A View From the Outside ... An interview with Erasmus alumnus and ESA astronaut Matthias Maurer

Dr Maurer, you once said that your Erasmus year at the University of Leeds in 1993 might have been the starting point of your journey into space. Why was this time so important for you?

Matthias Maurer: Leeds was my first experience of studying abroad, and it felt like a leap into the unknown. As an aspiring engineer, one of the things I wanted to do was improve my English. But going abroad with Erasmus came with a lot of questions: Would I be able to handle the experience? What would life in Leeds be like? What would I learn? Would it fit in with my study programme, or would I be wasting a year? I decided to take the plunge, and my time in Leeds turned out to be an incredibly positive experience. It encouraged me to spend more time abroad and I also studied in France and Spain. Early on, I learned the value of international collaboration, which is crucial in my work as an astronaut.

In what specific ways did your Erasmus experience in England impact you?

The University of Leeds introduced me to a different approach to learning. There was a lot of work in small groups, comparatively little theory and a strong focus on practical understanding. They concentrated on teaching the essentials, and much of what I learned has stuck with me to this day. It shows how important it is not to overwhelm students with too much material.

How did you adapt to life in England?

Sharing accommodation with four English students and two Canadians was really helpful. It took a week or so for us to get to know each other, but after that I really felt at home. I’m still in touch with my former flatmates even today. My time in England definitely broadened my perspective of Europe, too.

In what way?

Back then, I could hop on my motorbike and travel to England with just my German ID card – no problem at all. On a recent trip to the UK, I realised this isn’t so easy any more. Brexit has taken away the ease and freedom of the German-British exchange I was once able to enjoy. European exchanges have a special significance for me. Coming from Germany’s Saarland region, I visited the Verdun memorial in neighbouring France at an early age, which commemorates one of the worst battles of the First World War. War and conflict are one way of confronting differences with your neighbours. In England, I learned how to connect with people from a different culture, with a different language. It was a lesson in how peaceful coexistence within a united Europe is possible.

You mentioned that after your time at the University of Leeds, you also got to know France and Spain better through your studies. What were your experiences like in each of these countries?

In France, I encountered a very different academic approach with a heavy emphasis on theory, particularly in maths, physics and technical mechanics. This was quite a struggle for me. After things had gone so well in England, I anticipated a similar experience at the European School for Materials Technology in Nancy. But my time in France wasn’t only academically challenging. My school French was very limited at first, so it was hard to feel at ease and settle in straight away. It took time to adjust.

And how was it in Spain?

The focus on both practice and theory was very similar to what I had experienced in Germany, which made it easier for me to settle in. I had to learn Spanish first, but that came to me fairly quickly. I found that the curriculum at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona was similar to the programme at my home university, Saarland University. The exceptional warmth and openness of the Spanish people also helped me settle in. I can honestly say that each of my European study experiences was fantastic – every country taught me valuable lessons that have contributed to my growth and development.

And what about your career as an astronaut?

I believe my European experiences played a significant role in my selection by the ESA (European Space Agency). Of 8,500 candidates, only eight, including myself, were chosen. From a technical and academic point of view, probably most of the 8,500 candidates were qualified, but I think my strong European background gave me an important advantage.

Ich denke, mein europäischer Weg war ein entscheidender Baustein für meine Auswahl durch die ESA (European Space Agency).

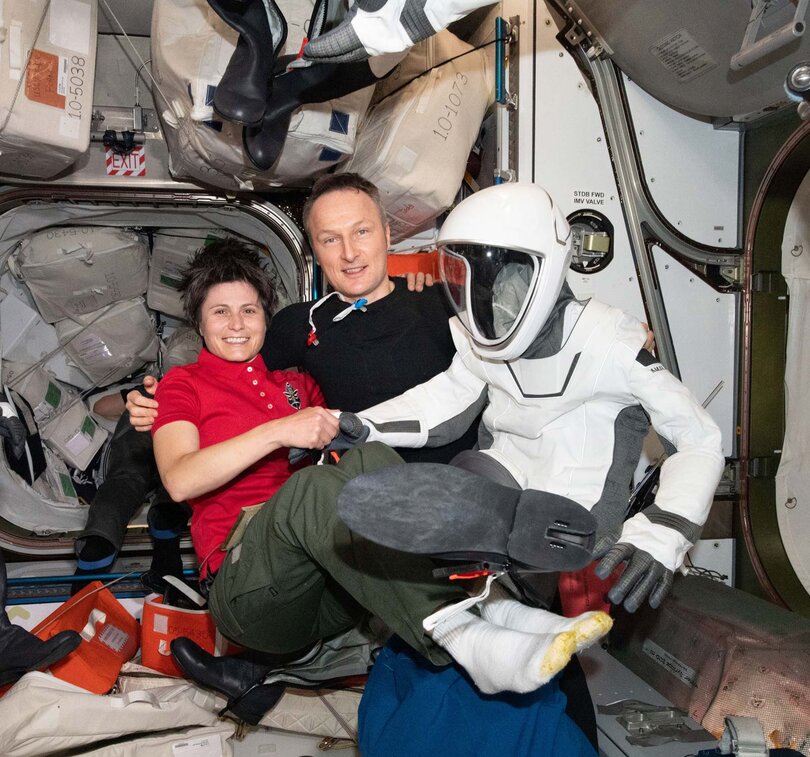

In 2022, for the first time, two ESA astronauts were on board the ISS simultaneously: Italian Erasmus alumna Samantha Cristoforetti and Matthias Maurer.

So does an ESA astronaut require a European mindset?

Let me illustrate this with a perspective from space. As an astronaut, you circumnavigate the Earth in around 90 minutes. It takes just five minutes to cross Europe. For Europeans to remain competitive on the global stage, we must work together. We have to strengthen our ties, and that means setting aside national sensitivities and things that may divide us historically. We must come together and build a unified European identity. Europe’s diverse countries, with their rich array of cultures and languages, represent a great strength. This diversity offers us advantages that can enhance our position over other space-faring nations.

Did studying in Europe help prepare you for your time on the International Space Station?

Yes, definitely, because when you spend six months living and carrying out research in space, social skills are crucial. In stressful and dangerous situations, you have to make sure the team functions harmoniously and effectively. If you approach this adventure only with a German perspective, this can be problematic. You have to be open to other outlooks too. And you have to communicate in order to minimise interpersonal tensions. No one arrives on the ISS with all the answers. Finding solutions requires collaborative effort. My international experiences helped me develop the necessary openness for this kind of teamwork.

How do scientists from different scientific backgrounds collaborate on the ISS?

In the laboratory, scientists can have different methods. For example, the American approach embraces the principle of «fail early, fail often». They almost want an experiment to go wrong so that lessons can be learned at an early stage. The German approach, on the other hand, aims to perfect experimental setups from the start. This can take years though, and may result in research questions being outdated by the time results are obtained. Finding a good balance between the different approaches is crucial. As a scientist in space, you have to adapt to new roles anyway.

Expedition 66 crew welcomes the three-person Soyuz MS-20 crew with Japanese spaceflight participant Yusaku Maezawa, Roscosmos cosmonaut Alexander Misurkin and Japanese spaceflight participant Yozo Hirano. 8 December 2021

What do you mean by that?

When you’re in space, you often work more as a lab technician than a scientist. It’s essential that you understand the objectives of the experiments you’re conducting. We have a huge responsibility to ensure that our colleagues on Earth receive the highest quality data. I’m acutely aware of the effort and dedication that scientists put into their work. An experiment can sometimes take ten years to prepare. Obviously, the last thing you want is to be the person who ruins everything with a single mistake.

What scientific goals are you focusing on next?

On the one hand, we’re closely monitoring the findings of ongoing experiments on the ISS. The unique conditions of weightlessness allow us to accelerate the development of these experiments for the ISS. Significant progress is being made in the field of medicine, where space-based research even has the potential to cultivate donor organs, which could address critical shortages on Earth. Our research is also shifting back to the Moon and Mars again.

What do you hope to gain from this?

Recent discoveries suggest that the desert planet of Mars may hold vast reserves of water ice. This finding is exciting because it could provide clues about whether life ever existed on Mars. We might even be able to find out more about the origins of life on Earth. The Moon could become a crucial springboard or future missions to Mars. Today, a journey to Mars would take two years, exposing space travellers to significant health risks, such as carcinogenic space radiation. This makes the Moon a potentially valuable stopover.

What else is there to discover on the Moon?

Water ice also exists on the Moon. It probably arrived there at the same time as water came to Earth. Studying the Moon could therefore deepen our understanding of life’s origins on our planet. Beyond that, the Moon holds valuable resources. One day, we might be able to extract oxygen from lunar sand to supply researchers. Potentially, we could even convert water ice into rocket fuel. The Moon could become a refuelling station for space missions. We’re already working on many of these topics at ESA’s Astronaut Centre in Cologne. We’re currently developing an ultra-modern lunar training facility, which we hope will provide groundbreaking insights.

You were on board the ISS on 24 February 2022, the day Russia launched its attack on Ukraine. How did that change your life on the ISS?

It was a terrible moment for all of us on the ISS. Lights in Ukrainian cities disappeared. From space, we watched as the country plunged into darkness. A black spot appeared in the heart of Europe. It was instantly clear to me that people’s lives there had changed drastically. It hit me hard; I couldn’t believe that something like this could happen in Europe today. I thought lessons from past wars had been learned.

What are your hopes for the future of Europe?

First of all, of course, peace! I want to see a Europe that continues to collaborate and remains united. Erasmus plays a key role in this. Given how quickly the world is changing, this is all the more important. Asian space-faring nations are about to overtake us. China already operates its own space station; India is developing a crewed space capsule and is also planning to build a station. South Korea and Japan are also very active. We Europeans need to step up our efforts to remain competitive in the top tier of space travel, helping to maintain our prosperity and quality of life. But our cooperation should go beyond science and technology – we must also strengthen our democracies. My greatest wish for Europe is that we continue to strengthen our ties and safeguard our democratic values at all times.

I want to see a Europe that continues to collaborate and remains united. Erasmus plays a key role in this. Given how quickly the world is changing, this is all the more important.

Many thanks for the interview.

In action in space and on Earth

Born in the German state of Saarland in 1970, Maurer studied materials science and materials technology at Saarland University, spending an Erasmus year at the University of Leeds in 1993 and periods at the European School for Materials Technology in Nancy and the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona. He earned several engineering degrees and completed a Master’s degree in economics for engineers at the FernUniversität in Hagen followed by a doctorate at RWTH Aachen University. Prior to his space mission, Matthias Maurer led the development of the new Luna simulation facility at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne. Since returning, he has been involved in many different ways in space exploration and research.

More photos of Matthias Maurer’s time on the ISS are available under:

A viewing window full of technology. The ESA – European Space Agency-built Cupola is our «window to the world» and the favourite place of many astronauts on the International Space Station. But in addition to an incredible view of the Earth, it also serves to observe robotic activities of the Canadian Space Agency robotic arm, arriving spacecraft & spacewalks. «When I first looked out, I first thought all the white was the sky, until I realised that it was the Earth, surrounded all around by the blackness of space. A jaw-dropping view!» 30 November 2021